Understanding Your Pelvic Floor Muscles: Anatomy and Function

Written by certified pelvic health physical therapists. Medically reviewed by board-certified specialists in urogynecology.

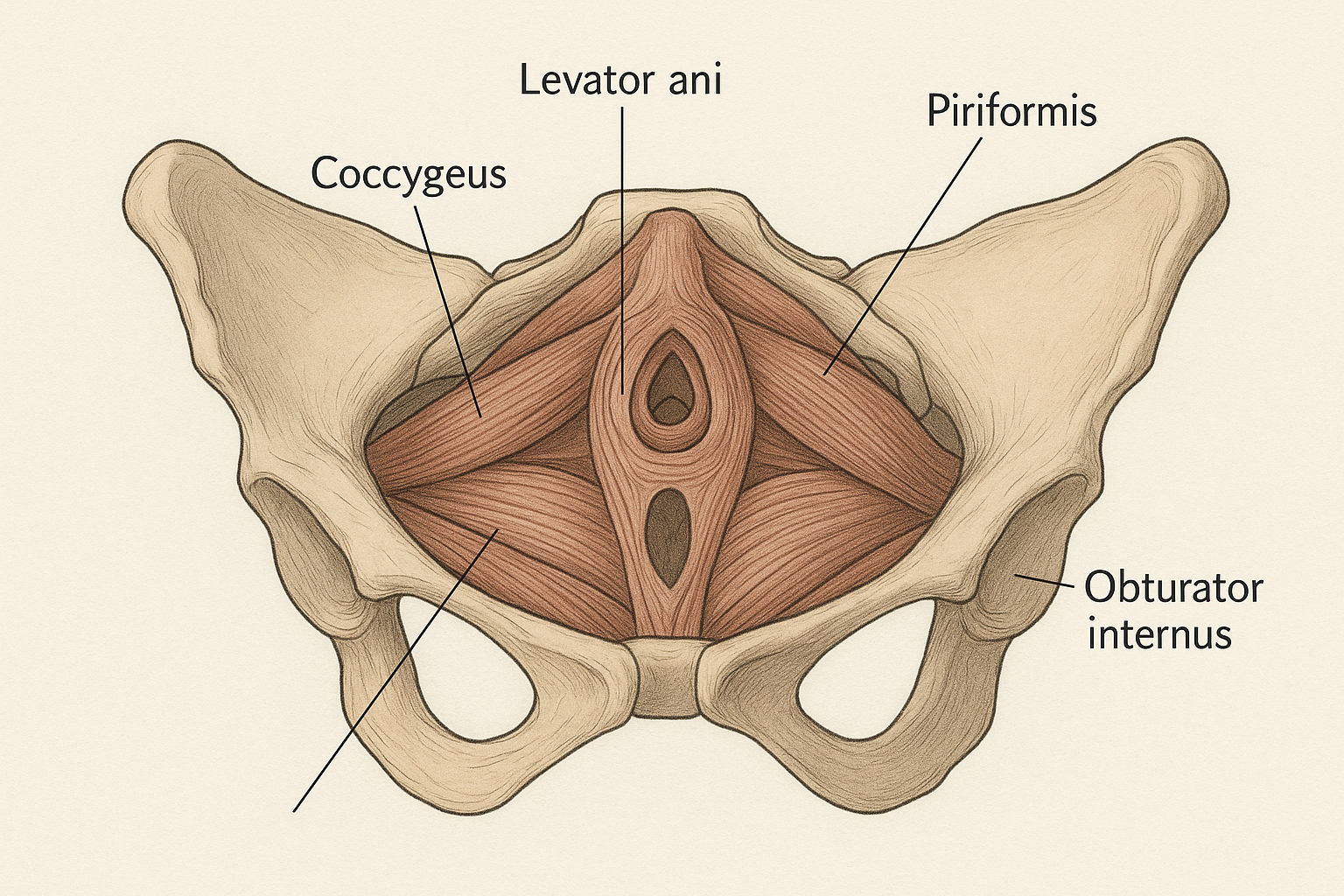

Detailed anatomical illustration of the pelvic floor muscles

What is the Pelvic Floor?

The pelvic floor consists of layers of muscles, tissues, ligaments, and fascia that stretch like a hammock from the pubic bone in front to the coccyx (tailbone) at the back, extending laterally from the ischial tuberosities (sitting bones) on each side. These muscles and tissues support the pelvic organs, including the bladder, intestines, and uterus (in women) or prostate (in men), against the forces of gravity and increases in intra-abdominal pressure.

Recent research has emphasized the importance of these muscles not just for bladder and bowel control, but also for core stability, sexual function, posture, and overall quality of life [1]. Despite their critical importance, the pelvic floor remains one of the least understood muscle groups in the human body, even among healthcare professionals. Understanding pelvic floor anatomy and function is essential for anyone experiencing related symptoms or seeking to optimize their pelvic health.

Anatomy of the Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor is not a single muscle but rather a complex three-dimensional network of muscles, connective tissue, and neural structures. Understanding this anatomy is crucial for properly performing pelvic floor exercises and for healthcare providers in diagnosing and treating related conditions.

The Primary Muscle Groups

The pelvic floor muscles include several key structures that work in coordinated fashion:

- Levator ani complex: The largest and most functionally significant muscle group of the pelvic floor, consisting of three main components:

- The pubococcygeus: Forms the main body of the levator ani and is crucial for pelvic organ support

- The puborectalis: Forms a sling around the rectum and is critical for bowel continence and maintaining the anorectal angle

- The iliococcygeus: Stretches from the lateral pelvic wall to the coccyx and contributes to overall pelvic support

- Coccygeus (also called ischiococcygeus): A triangular muscle that works with the levator ani to support the coccyx and lower sacrum, particularly important for spinal stability

- Superficial perineal muscles: Located at the surface of the perineum (the area between the genitals and anus), including:

- Bulbospongiosus: Surrounds the urethral opening in women and contributes to vaginal sensation; in men, assists with erection and ejaculation

- Ischiocavernosus: Compresses erectile tissue in the external genitalia; more developed in men

- Superficial transverse perineal muscle: Provides stability to the perineal body

- Anal sphincter complex: Comprising both the involuntary internal anal sphincter and the voluntary external anal sphincter, which work together to maintain bowel continence

- Urethral sphincter complex: Including the involuntary intrinsic sphincter and the voluntary external sphincter that control urine flow

Supporting Structures

The pelvic floor works as an integrated system with surrounding structures. The fascia (connective tissue covering) that envelops these muscles is highly innervated and contributes significantly to proprioception (awareness of body position). The ligaments supporting the pelvic organs—including the cardinal ligaments, uterosacral ligaments (in women), and the puboprostatic ligaments (in men)—work in concert with the muscles to maintain optimal organ positioning.

A landmark study by DeLancey (2005) provided detailed insights into how these muscles function together to maintain pelvic organ support [2]. More recent advanced imaging studies, including dynamic MRI and 3D ultrasound, have enhanced our understanding of the three-dimensional nature of these muscle groups and their dynamic coordinated action during various activities [3].

Neural Control and Innervation

The pelvic floor receives its nerve supply primarily from the sacral spinal nerves (S2-S4) through the pudendal nerve and the pelvic splanchnic nerves. This neural supply allows for both voluntary control (via the somatic nervous system) and involuntary regulation (via the autonomic nervous system) of pelvic floor function. The pelvic floor is unique in its dual innervation—unlike most voluntary muscles, the urethral and anal sphincters are continuously active at rest, maintaining a baseline level of muscle tone that keeps you continent.

Functions of the Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor muscles serve several interrelated and critical functions that span multiple body systems:

1. Organ Support and Prevention of Prolapse

The pelvic floor provides crucial support for the pelvic organs against gravity and increases in intra-abdominal pressure. Every time you cough, laugh, sneeze, or engage in physical activity, the pressure inside your abdomen increases dramatically. Weakened pelvic floor muscles can allow organs to descend from their normal position—a condition called pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Research indicates that up to 50% of women with children have some degree of prolapse, though symptoms vary widely [4]. The severity ranges from asymptomatic (requiring no treatment) to severe cases where prolapsing organs cause significant discomfort and functional impairment.

2. Continence Control

The pelvic floor muscles are essential for maintaining continence for both urine and feces. For urinary continence, these muscles work with the urethral sphincters to prevent involuntary urine loss during increased abdominal pressure (stress incontinence). The pubococcygeus portion of the levator ani can actively contract to increase urethral closure pressure when needed—for instance, when you feel the urge to urinate between bathroom visits. For fecal continence, the puborectalis maintains the anorectal angle (the natural bend in the colon at the rectum), and the external anal sphincter provides voluntary control. A systematic review found A systematic review found that up to 33% of women experience urinary incontinence, with stress incontinence being the most common type, and it's a significant but often underreported issue in men as well [5].

3. Sexual Function and Sensation

The pelvic floor muscles play a significant role in sexual function and satisfaction for both men and women. In women, these muscles contract rhythmically during orgasm and contribute to vaginal sensation and lubrication through their association with vascular and neurological structures. Strong pelvic floor muscles can enhance sexual sensation and the intensity of orgasmic contractions. In men, the bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus muscles are critical for maintaining erectile function by compressing venous outflow from the erectile tissue, and they also contract during ejaculation to propel semen through the urethra. Research shows that pelvic floor strength directly correlates with sexual satisfaction in both genders [6].

4. Core Stability and Posture

Along with the transversus abdominis (deep abdominal muscles), diaphragm, and multifidus (deep back muscles), the pelvic floor contributes to core stability and intra-abdominal pressure regulation. This integrated system is crucial for spine stabilization during movement, maintaining proper posture, and preventing lower back pain. Research has demonstrated that individuals with lower back pain often have pelvic floor dysfunction, and addressing both issues provides better treatment outcomes [7]. The pelvic floor also plays a role in respiratory function, as it must coordinate with the diaphragm during breathing to maintain optimal core pressure.

5. Lymphatic and Circulatory Support

The pelvic floor muscles contribute to lymphatic drainage and circulatory function in the pelvic region. Muscle contractions act as a pump that helps circulate fluid and blood through the pelvic organs. This is particularly important for sexual health, as adequate blood flow is essential for sexual arousal and function.

Common Pelvic Floor Disorders

Dysfunction of the pelvic floor can manifest in various ways. Understanding these conditions is important because they're often underdiagnosed and undertreated due to stigma and lack of awareness among both patients and healthcare providers.

- Stress urinary incontinence (SUI): Leakage of small amounts of urine during activities that increase abdominal pressure, such as coughing, sneezing, laughing, or exercise. This is the most common type of incontinence in women and is increasingly recognized in men, especially post-prostatectomy.

- Urgency urinary incontinence: Sudden, involuntary loss of urine accompanied by a strong urge to urinate. Often relates to overactivity of the detrusor muscle (bladder muscle) rather than pelvic floor weakness, though pelvic floor dysfunction can contribute.

- Mixed urinary incontinence: A combination of stress and urgency components; very common in older adults.

- Pelvic organ prolapse (POP): Descent of pelvic organs (bladder, uterus, rectum) from their normal position due to weak pelvic floor support. Can cause symptoms ranging from a feeling of heaviness or pressure to pain with sexual intercourse or difficulty with bowel movements.

- Fecal incontinence: Inability to control bowel movements, ranging from occasional staining to complete loss of control. Can result from pelvic floor weakness, nerve damage, or anal sphincter dysfunction.

- Pelvic pain syndromes: Including vulvodynia (chronic vulvar pain), vaginismus (involuntary contraction of vaginal muscles), and chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men. Often involve excessive tension or trigger points in pelvic floor muscles.

- Sexual dysfunction: Including dyspareunia (pain during intercourse), erectile dysfunction in men, and difficulty achieving orgasm in both genders. Can relate to both weakness and excessive tension in pelvic floor muscles.

- Chronic pelvic pain: Persistent pain in the pelvic region, sometimes associated with pelvic floor myofascial dysfunction (trigger points and muscle tension).

A systematic review by Wu et al. (2018) found that pelvic floor muscle training is effective as a first-line, non-invasive treatment for many of these conditions [4]. In fact, major medical organizations including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Urological Association recommend pelvic floor muscle training as the first-line treatment for stress incontinence, before considering medication or surgery.

Risk Factors for Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Certain factors increase the risk of developing pelvic floor problems:

- Pregnancy and vaginal childbirth (trauma to pelvic floor muscles and nerves)

- Aging and hormonal changes (menopause, andropause)

- Chronic constipation and straining (places excessive load on pelvic floor)

- Chronic cough (smoking, asthma, COPD)

- Heavy lifting and strenuous exercise without proper core engagement

- Obesity (increased intra-abdominal pressure)

- Pelvic surgery or radiation therapy

- Neurological conditions (spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis)

- Chronic pelvic pain conditions

- Sedentary lifestyle and poor posture

Importance of Pelvic Floor Exercises

Regular pelvic floor muscle training (Kegel exercises) can help prevent or treat many of the conditions listed above. Benefits include:

- Prevent or reduce urinary and fecal incontinence

- Support recovery after childbirth and pelvic surgery

- Improve sexual function and satisfaction

- Provide support before and after major pelvic procedures

- Enhance core stability and posture, potentially reducing back pain

- Improve exercise performance and athletic ability

- Maintain pelvic health proactively, preventing age-related dysfunction

The PelvicFit app offers guided exercises that target these muscles specifically using clinically validated protocols, with programs tailored to different needs, goals, and conditions. Research shows that structured, guided training yields superior outcomes compared to self-directed exercises without professional guidance [8].

When to Seek Professional Help

While many people can benefit from home pelvic floor training, certain situations warrant professional evaluation:

- If you're unable to identify or contract your pelvic floor muscles despite instruction

- If symptoms persist despite 4-6 weeks of consistent home training

- If you experience pelvic pain that limits your ability to exercise

- If you have significant incontinence affecting your quality of life

- If you've had pelvic surgery and need specialized rehabilitation

- Before and after major urologic or gynecologic procedures

A pelvic floor physical therapist can provide personalized assessment, biofeedback training, and specialized manual therapy techniques that can significantly enhance treatment outcomes. The PelvicFit app can serve as an excellent complement to professional care, providing structured home exercise programming between therapy sessions.

Conclusion

Understanding the anatomy and function of your pelvic floor muscles is the first step toward maintaining their health and addressing any related issues. The pelvic floor is far more complex and functionally important than most people realize, yet this complexity makes it an area ripe for effective intervention. Whether you're looking to prevent problems, recover from childbirth or surgery, optimize athletic performance, or address existing symptoms, a consistent program of properly performed pelvic floor exercises can significantly improve your quality of life across multiple dimensions—from continence and sexual function to posture and pain management.

The key to success is understanding that your pelvic floor is not a "set it and forget it" system but rather requires ongoing attention and maintenance throughout your life, much like other important muscle groups. With proper guidance and regular practice, virtually anyone can achieve measurable improvements in pelvic floor function and overall well-being.

Anatomy of the Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor muscles include several key muscle groups:

- Levator ani: The largest muscle group of the pelvic floor, consisting of the puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and iliococcygeus muscles.

- Coccygeus: A triangular muscle that supports the coccyx and lower sacrum.

- Superficial perineal muscles: Including the bulbospongiosus, ischiocavernosus, and superficial transverse perineal muscles.

- Anal sphincter complex: The internal and external anal sphincters.

- Urethral sphincter complex: The intrinsic and extrinsic urethral sphincters.

A landmark study by DeLancey (2005) provided detailed insights into how these muscles function together to maintain pelvic organ support [2]. More recent imaging studies have enhanced our understanding of the three-dimensional nature of these muscle groups and their coordinated action [3].

Functions of the Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor muscles serve several critical functions:

Support

The pelvic floor provides crucial support for the pelvic organs against gravity and increases in intra-abdominal pressure. This support is essential for preventing pelvic organ prolapse, a condition where organs descend from their normal position.

Sphincter Function

These muscles help maintain continence by controlling the release of urine and feces. The pubococcygeus portion of the levator ani and the external urethral sphincter are particularly important for urinary continence.

Sexual Function

The pelvic floor muscles play a significant role in sexual function for both men and women. In women, these muscles contract during orgasm and contribute to vaginal sensation. In men, they contribute to erectile function and ejaculation.

Stability

Along with the transversus abdominis, diaphragm, and multifidus, the pelvic floor contributes to core stability and intra-abdominal pressure regulation, which is important for spine stabilization during movement.

Common Pelvic Floor Disorders

Dysfunction of the pelvic floor can lead to various conditions, including:

- Stress urinary incontinence: Leakage of urine during activities that increase abdominal pressure

- Pelvic organ prolapse: Descent of pelvic organs from their normal position

- Fecal incontinence: Inability to control bowel movements

- Chronic pelvic pain: Persistent pain in the pelvic region

- Sexual dysfunction: Including pain during intercourse (dyspareunia)

A systematic review by Wu et al. (2018) found that pelvic floor muscle training is effective as a first-line treatment for many of these conditions [4].

Importance of Pelvic Floor Exercises

Regular pelvic floor muscle training (Kegel exercises) can help:

- Prevent or reduce urinary and fecal incontinence

- Support recovery after childbirth

- Improve sexual function and satisfaction

- Provide support before and after pelvic surgery

- Enhance core stability and posture

The PelvicFit app offers guided exercises that target these muscles specifically, with programs tailored to different needs and conditions.

Conclusion

Understanding the anatomy and function of your pelvic floor muscles is the first step toward maintaining their health. Whether you're looking to prevent problems, recover from childbirth or surgery, or address existing symptoms, a consistent program of properly performed pelvic floor exercises can significantly improve your quality of life.

References

- Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. Functional anatomy of the female pelvic floor. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1101:266-296.

- DeLancey JO. The hidden epidemic of pelvic floor dysfunction: achievable goals for improved prevention and treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1488-1495.

- Dietz HP. Pelvic floor ultrasound: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):321-334.

- Wu YM, McInnes N, Leong Y. Pelvic floor muscle training versus watchful waiting and pelvic floor disorders in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24(2):142-149.